| Thirty years after arrival

of democracy, Poland's facing deep divisions

In the summer of 1989, Poles united

under the Solidarity movement (Solidarność) achieved a crucial democratic

breakthrough by obtaining the hold of elections from the communist regime.

Thirty years after, noted our contributor, a fratricidal conflict is tearing

apart the great trade union, an illustration of a country torn between

nationalist and pro-European camps.

Gdansk - It was in September 1980.

The Solidarity trade union was just born and Anna Maria Mydlarska, a young

witness from the beginning, was not even close to imagine the scope of

the event: a month later, no less than 10 million of Poles joined to the

movement which would hasten the fall of communism.

"There was an infectious enthusiasm

in the society", said the film-maker who became the interpreter of Lech

Wałęsa, a living icon of the movement. "It was more than a simple trade

union: the intellectuals, professors and students, members of Sciences

Academy... The dissidence was everywhere, it was amazing."

Through the window of her office

in the European Solidarity Centre - a separate organization from the Solidarity

trade union - we can see the rusted crane of the famous shipyards of Gdańsk.

It is in this port city, bordered by the Baltic Sea, that was born the

first independent trade union of the communist bloc, which became the engine

of a unified civil society around the same objective: to get rid of autocracy.

The triumph came in 1989. On June

4th of that year, a rare democratic opening happened, while the regime

of the general Wojciech Jaruzelski authorized the first partially-free

elections in the country. Enough do provoke a craze in the rest of the

bursting Eastern bloc, on the verge of bursting. Six month later, on November

9, the Berlin Wall was falling.

Fratricidal Battle

On the floor below, still in the

European Solidarity Centre, Lech Wałęsa, who is now 75, has not lost his

shape. Neither his mustache. Backed by a portrait of Pope John Paul II

and surrounded by European and Polish flags, the central figure of the

80's movement regrets nothing. "My role was to bring freedom to society",

said the trained electrician who became President of the republic in 1990.

"And that is what I did: it allowed to erase borders in Europe."

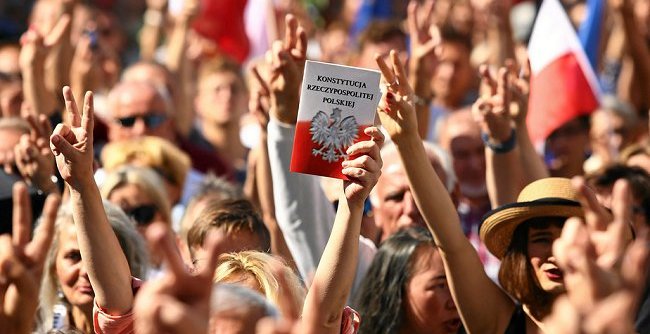

On his shirt, the word "Konstytucja"

(Constitution in polish) is written, a way for him to oppose the power

currently in place in Warsaw "even in my dressing style". In an open conflict

with the ruling party Law in Justice (PiS), headed by Jarosław Kaczyński

since 2015, Lech Wałęsa is portrayed by the government as a true enemy,

accused of having been an "agent" of the communist power.

Today, a fratricidal battle opposes

the two man, like a country mainly torn between nationalist and liberal

pro-European camps. On one hand, there are supporters of the PiS, an ultraconservative

party accused of breaking the rule of law and enforce historical revisionism.

On the other, opposition circles are criticized to be disconnected from

the grass-root people.

'He is a dishonest man", said M.

Wałęsa, referring to Jarosław Kaczyński, himself a former member of the

Solidarity movement. "He can't position himself politically than with populism

and demagoguery, it's his tactic to stay in power."

"Betrayal" of the elites

Two streets further, at the Solidarity

union headquarters, a now PiS-controlled institution, opinions differ.

"We do have a lot of reasons to be satisfied with the policies of the current

government", said Bogdan Olszewski, secretary of the Gdańsk region, praising

the social aids that the PiS has established since 2015.

For the elected PiS deputy and former

president of the trade union Janusz Śniadek, "It is the workers and old

members of Solidarity that lost during the transition". He said that a

certain feeling of betrayal toward liberal elites" persists in the country.

"Wałęsa tells that he defeated communism alone, but he never thanked the

other members of the movement", said Mr. Śniadek.

Marcin Darmas thinks the same. For

this conservative sociologist at the Warsaw University, the social divides

could be explained in part by the 1989 round table agreements, which resulted

in a regime transition. According to him, the "excluded" of the transition

would now see the PiS as their main moral support. "The great figures of

the movement were the privileged ones. But for others, justice has not

been done."

"The political climate in Poland

is toxic", said the Vice mayor of Gdańsk, Piotr Grzelak. Last January,

at a charity event in this peaceful city of one million people, the mayor

of the time Paweł Adamowicz was murdered by an unbalanced man. For Mr.

Grzelak, there is no doubt that "the level of discussion reached a point

where people, whether crazy or not, come to the idea of killing someone

for political reasons".

The current climate is even tearing

families apart, says the politician of the opposition. "Today, at table,

people avoid political discussions. It is up to both sides to ease tensions

in this context."

Authoritarian slide?

The political transformation for

30 years has been imperfect, admits for his part the journalist Konstanty

Gebert. "But during that time, the communists did not intend to negotiate

their own end. That's what started an irreversible transition to democracy",

he said.

However, 30 years later, this atmosphere

of unity has disappeared. "What is very disturbing is that this division

in Poland is deep and binary."

And he thinks that the PiS has his

share of responsibility in this context by claiming a certain "monopoly"

of the values and the popular representation. "Thus, the PiS creates a

division that has existed neither in the last 30 years of democracy nor

under the communist regime" regrets this former influential member of the

union, who participated in the negotiations of the round table.

In the wake of the parliamentary

elections to be held in autumn, he fears that an "illiberal" democracy

will emerge in Poland, like in Hungary. With a 45% score in the European

elections last May, the PiS is heading for another victory, he redoubts.

"If they get the constitutional majority, it's the end of the democratic

game."

The road toward democracy

1980 After many strikes in

front of the shipyards of Gdansk, the workers obtain the right to gather

together behind the Solidarity trade union, with Lech Wałęsa as the leader.

1981 Driven by Moscow, the

martial law is implanted in Poland. The repression goes again. Many of

Solidarity members are imprisoned, but the movement keep operating in the

clandestinity.

1989 Around the famous round

table, communists and representatives of Solidarity negotiate a peaceful

democratic transition. In June, Solidarity won the first semi-democratic

parliamentary elections, five months before the fall of the Berlin Wall.

1990 Lech Wałęsa is elected

President of the Republic and abandons the Presidency of Solidarity.

Patrice Senécal

This text is a translation of

a story originally published in La Presse, on August 10th, 2019 (Pologne:

trente ans apres la démocratie, la division).

Patrice Senécal - is a young

free-lance journalist who contribute occasionally to some Quebec newspapers

and Le Courrier d'Europe centrale, a French portail that covers Central

Europe. Currently learning Polish and Spanish, curious by nature, he loves

to search and tell stories that that goes beyond the news. He currently

study in a political science program at Université de Montréal.

|