| Memory is our Homeland

When talking about the beginning

of World War II there is a small, yet significant fact, usually overlooked;

Poland was not only attacked by Germany, but on 17th September 1939

it was also invaded by the Soviet Russia from the East, and it is here

that this story begins.

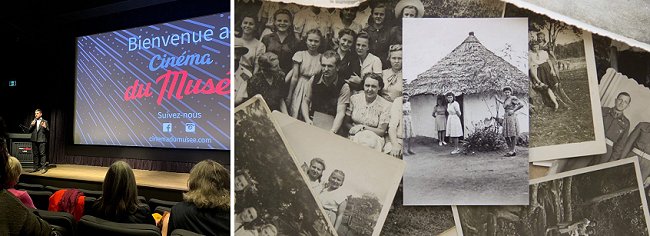

The movie "Memory is our Homeland",

which was screened at the Cinéma du Musée in Montreal gives an insight

into what life was like for those in Poland during the Russian invasion,

and what happened to them afterwards. The film director is Jonathan Durand.

It was his personal journey deep back into the history of his family and

the Polish people in general, during World War II. Poland as it was then,

no longer exists. The film plot starts in a small village-like town of

Ostrówek (now part of Belarus).

It was from there that eighty years

ago, the Durand family was forcibly taken to Siberia. Later, like many

others, the grandma and aunt of the Durand family went to Iran, Central

Asia, and finally found themselves in a Polish refugee camp in Africa.

Even today, this kind of Polish war stories is not well-known.

I have to admit that the film made

a huge impression on me, I heard about the deportations to Siberia, Katyń,

labor camps, but I was made aware of the existence of Polish refugee camps

in Africa (between 1942 and 1952) thanks to this movie. I would like to

give my thanks to the film director for sharing this story with us in a

form of such a beautiful, moving documentary.

It was there, far away from their

Homeland, that those deported from Poland tried to regain their dignity

and live in harmony again, trying to live with the memory of what had happened

and all that they had lost.

The story has a very personal touch

and is told from the perspective of the directors late grandmother, Kazimiera

Kołodziej, who appears in the film several times. It is clear from her

testimony that, although she was forcibly uprooted from Poland at a young

age, it always remained her home, and wherever she would go it never

felt the same. On arrival in Africa, they were greeted warmly and finally

had the opportunity to restore a semblance of a peaceful life. Even though

she finally felt safe, she would never consider it home and longed to return

to her homeland.

The refugee camps in Uganda, Kenya,

Zambia, Zimbabwe, Tanzania and South Africa were in fact shelters for many

Polish women and children who were sent there. Initially a settlement with

a couple huts in which they lived, was eventually changed into their own

place with their schools, churches and hospitals.

Durand visited Africa, and many other

places of tragic history, looking for memories, photos, places where his

grandmother, aunt and other relatives lived.

The camp residents maintain these

camps still house people who remember their Polish guests; the film shows

us some of the photographs, documents and even a cemetery for Polish refugees

as well as the first-hand accounts from the new arrivals back then.

Thanks to the documentary film maker

we discover contemporary Africa, and thanks to family stories and recently

discovered old photographs (some of which with the image of the directors

grandmother) the previously unknown story unfolds.

While watching the film sometimes

I had the impression this was some sort of surreal tale or pure fantasy.

Who could have known that somewhere in exotic Africa, during and after

the war, there were Poles, exiles, whom the external world could have seemingly

forgotten?

Yet, after the war, the Poles left

Africa and were dispersed in various different countries, including England

and Canada. There they built houses, started families, and somehow regained

peace.

And sometimes, with tears in their

eyes and a shrill voice, they would tell their children and grandchildren

their painful histories, so far unknown. Without these stories and the

determination of Jonathan Durand to show them to the world, the film would

not have certainly been made; thus one more story would have remained buried

forever.

The reaction of the viewers, after

the film ended, shows that not only I think that it is a priceless documentary

which needs to stay alive in everyones memory.

My hope is that the documentary will

be shown in as many places as possible, so that people remember those who

suffered and endured so much. Despite the misery and pain that this world

brings to us, I am happy that at last a handful of my countrymen were able

to find peace and live a happy life.

Katarzyna Knieja

Katarzyna Knieja - pedagog z

wykształcenia, trochę niedzisiejsza miłośniczka kultury wszelakiej, podróżowania,

natury i zwierząt. Ze swej pasji uczyniła zawód, na co dzień zajmuje się

opieką nad czworonożnymi pupilami mieszkańców Montrealu i sprawianiem,

by jej życie miało sens. Posiadaczka ubóstwianego psa o wdzięcznym imieniu

Thor.

|